Why Do Historians Primarily Use The Bible To Understand Who the Historical Jesus Was?

Isn’t the Bible biased? Shouldn’t historians be using non-Christian sources as well to uncover what the historical Jesus said and did? Are these scholars simply Christians trying to prove that Jesus was the Messiah?

Let’s begin with the non-Christian writings about Jesus. There are only three of them (possibly four) composed within roughly a hundred years of his death. Anything later than that is usually too far removed to be of much help. They are:

Josephus — A Jewish historian writing in the late first century.

Tacitus — A Roman senator and historian of the early second century.

Pliny the Younger — A Roman governor and letter-writer of the early second century.

Suetonius (a possible reference) — A Roman historian and biographer of the early second century.

That is the entire list. Of course, these were not necessarily the only non-Christians who ever wrote about Jesus; they are simply the only references that have survived. Ancient texts were often lost, and it is entirely plausible there were others that did not make it down to us.

Still, three (or four) references are not nothing. Yet these writers say very little. Josephus says the most, but even his remarks fall far short of the detail found in the canonical Gospels—and those are themselves limited. His passages about Jesus also raise difficulties: the surviving manuscripts show signs of later Christian editing, especially where Jesus is explicitly called the Christ, a claim unlikely to have come from a non-Christian Jew.

To see how little these authors provide, consider the passage from Tacitus:

But neither human resources, nor imperial munificence, nor the appeasement of the gods, eliminated sinister suspicions that the fire had been instigated. And so, to dispel the rumor, Nero substituted as culprits, and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilatus, and the deadly superstition was checked for a moment, only to break out once more, not merely in Judaea, the home of the disease, but in the capital itself, where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and become fashionable…

— Tacitus, Annals 15.44 (trans. J. Jackson, Loeb Classical Library, 1937).

Tacitus tells us very little about Jesus himself. He notes only that:

Jesus (whom he calls Christus) was the founder of Christianity.

He was executed under Pontius Pilate during the reign of Tiberius.

His movement began in Judea and later spread to Rome.

Pliny the Younger and Suetonius contribute even less. Suetonius is uncertain, because he refers to disturbances “at the instigation of Chrestus,” which some think is a misspelling of Christus. He writes:

He [Claudius] utterly abolished all foreign rites, especially the Egyptian and the Jewish, compelling those who practiced such superstitions to burn their religious vestments and all their paraphernalia… He banished from Rome all the Jews, who were continually making disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus.

— Suetonius, Life of Claudius 25.4 (trans. J. C. Rolfe, Loeb Classical Library, 1914).

If Suetonius did mean Jesus and his followers here, he must have meant “in the name of Chrestus,” because Jesus was long dead by Claudius’s reign. Either way, the reference tells us nothing about Jesus’ life.

In short, we would like more non-Christian sources, but the ones we have are too sparse to reshape our understanding of Jesus’ words or actions in any meaningful way.

Are there any other early references? There are, and they are non-biblical Christian writings—often called the apocrypha:

Gospel of Thomas (2nd century): A collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus, some overlapping with the canonical gospels, others unique and mystical.

Gospel of Peter (2nd century): A fragmentary account of the Passion and Resurrection, filled with cosmic imagery and a dramatic empty tomb scene.

Infancy Gospel of Thomas (2nd century): Tales of Jesus’ childhood, often portraying him as a wonder-working yet sometimes unsettling figure.

Gospel of Mary (Magdalene) (2nd century): Highlights Mary Magdalene’s visions and teachings, granting her striking authority among the disciples.

Gospel of Judas (2nd century): Recasts Judas not as a traitor but as the disciple who alone understood Jesus, with his “betrayal” portrayed as obedience to Jesus’ plan.

Acts of Peter (late 2nd century): Narratives of Peter’s preaching, miracles, and martyrdom.

Why not rely on these texts for the historical Jesus? In some cases—especially the Gospel of Thomas—scholars do. But overall, they carry less weight than the canonical Gospels or Paul’s letters. The reason is that most of them were written later and depend on the earlier texts. That makes them both late and derivative—two qualities that weaken their usefulness for reconstructing history.

When we say these texts are “dependent,” we mean that their authors already knew the New Testament and borrowed from it. If the Gospel of Thomas repeats a parable from Matthew, it does not give us independent confirmation; it simply echoes the earlier text. Historical study values sources that can stand on their own, not copies.

But the Gospel of Thomas is still the notable exception. Some of its sayings may reflect very early traditions, independent of the canonical gospels. But much of it likely comes from a later period, shaped by Gnostic thought and literary borrowing. That makes it hard to separate authentic early material from later reinterpretation. For that reason, it remains a secondary source: potentially useful, but not as central as Paul or the Synoptic Gospels.

This leaves us, above all, with the Bible. Historians rely on it because, despite its clear bias (it was written by believers for believers) it is what we have. But bias does not render a source worthless. Scholars apply methods such as the “criterion of embarrassment,” which argues that details unfavorable to the early church are unlikely to have been invented. For example, all three synoptic Gospels report that Jesus was baptized by John the Baptist. John's Gospel doesn't mention Jesus' baptism by John, but it does describe John the Baptist testifying that he saw the Spirit descend upon Jesus. The baptism could imply that John was superior to Jesus (as he is the one doing the baptizing), or that Jesus required forgiveness of sins—neither message would serve Christian theology. The tradition appears across all four Gospels, whether narrated directly or acknowledged indirectly, which points to its early and widespread acceptance. The same is true of reports that Jesus was rejected in his hometown: the humiliation does nothing to enhance his stature, but it makes sense as a stubborn historical fact.

So yes, the Bible is biased, but that does not make it useless. Non-Christian references confirm little more than Jesus’ existence and execution, and the apocryphal writings mostly rework earlier traditions. What we are left with are the Gospels and Paul, texts written by believers but close in time to the events. Read critically—with tools like the criterion of embarrassment—they give us our best access to the historical Jesus. Without them, we would know almost nothing at all.

Works Cited

The Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version.

Josephus, Flavius. Jewish Antiquities. Translated by H. St. J. Thackeray. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1930.

Pliny the Younger. Letters. Translated by Betty Radice. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1969.

Suetonius. Lives of the Caesars. Translated by J. C. Rolfe. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1914.

Tacitus. Annals. Translated by J. Jackson. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1937.

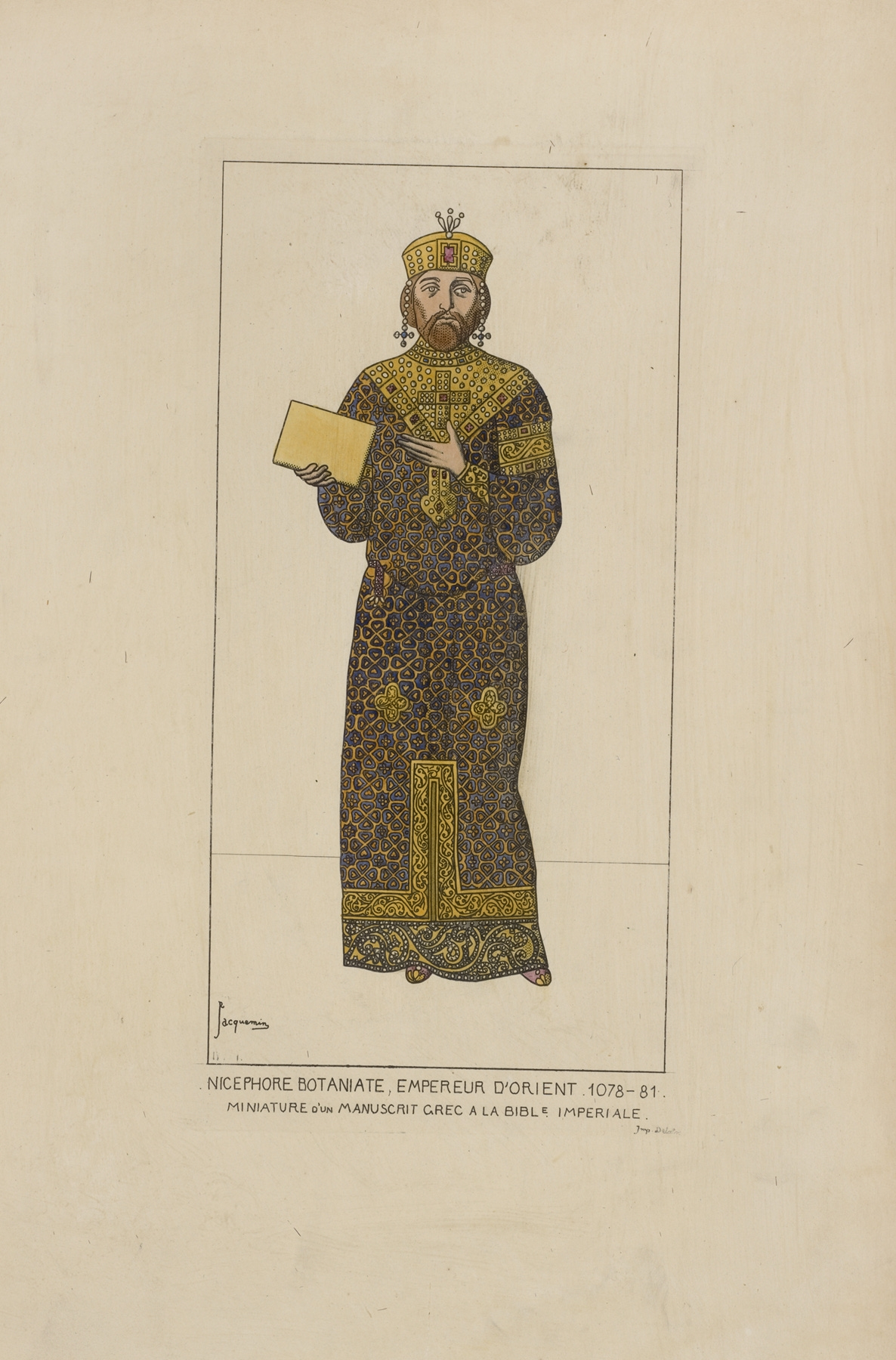

Jacquemin, Raphaël (French, 1821–1881). Nicephore Botaniate, Empereur d’Orient 1078–81. Miniature d’un manuscrit Grec a la Bible Imperieale. 1869. Lithograph.

So little survives outside the early Christian story, yet the memory of Jesus endures. What is remembered and passed down tells us as much about those who remembered as about Him. The texts become a lens that shows us glimpses of a life that moved people, the weight of belief, and the traces of what truly mattered and still matters to this day.