Secret Messiah

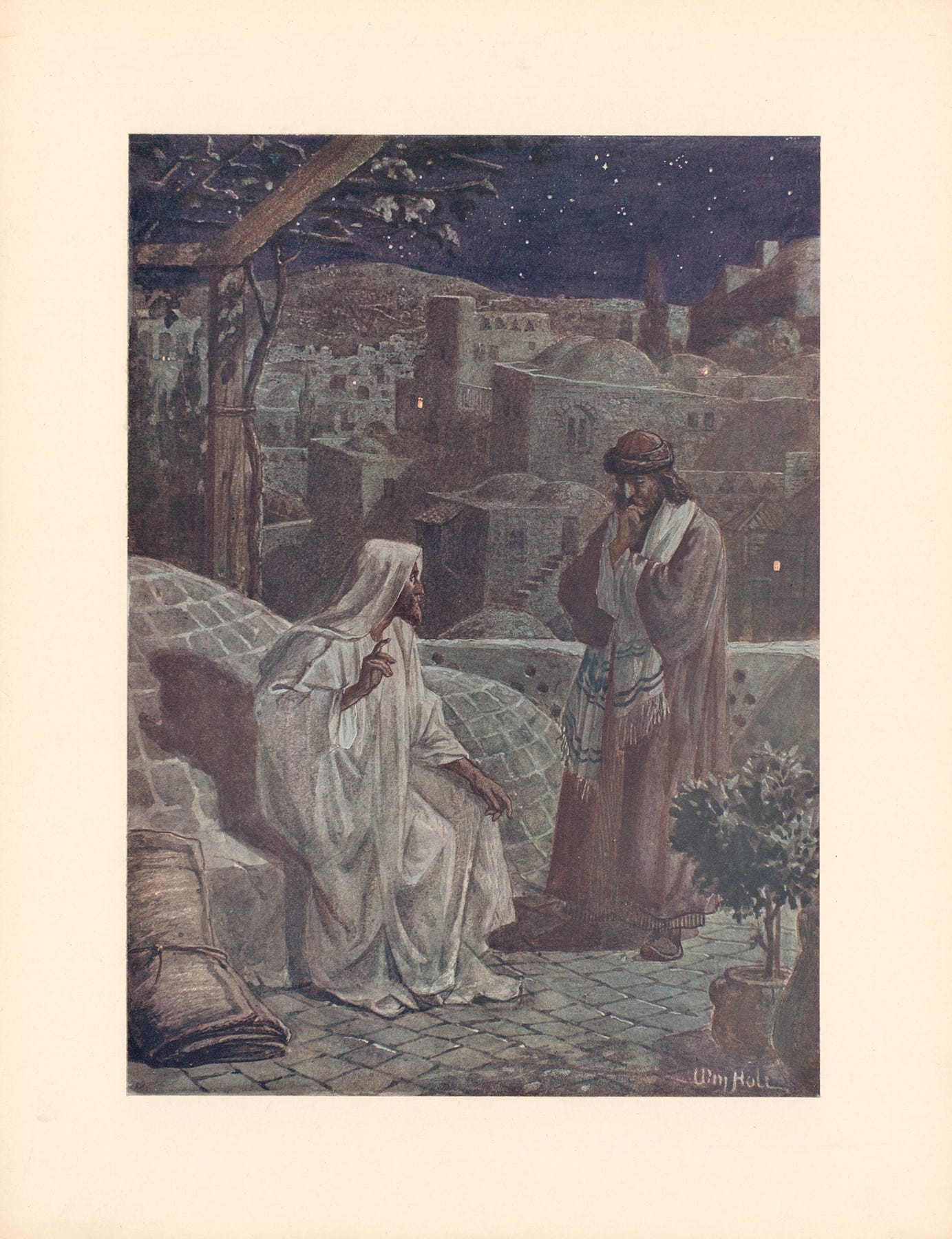

Nicodemus comes to Jesus by night (20th century). William Hole (English, 1846 – 1917)

If you read the Gospel of Mark straight through, a pattern forms: Jesus repeatedly attempts to conceal his identity and his works. He demands silence after exorcisms, healings, confessions, and even visionary experiences. Scholars often call this motif the “Messianic Secret,” and Mark presents it with unusual intensity. Observe:

He sternly ordered the disciples not to tell anyone about him.

—Mark 8:30

He healed many who were sick and cast out many demons, and he would not permit the demons to speak, because they knew him.

—Mark 1:34

He sternly charged the man and sent him away at once, saying that he should say nothing to anyone.

—Mark 1:43–44

Whenever the unclean spirits saw him, they fell down before him and cried out that he was the Son of God, and he strictly ordered them not to make him known.

—Mark 3:11–12

After raising the girl, he strictly ordered them that no one should know this.

—Mark 5:43

He ordered them to tell no one; but the more he ordered them, the more zealously they proclaimed it.

—Mark 7:36

He sent the man home, saying he was not even to go into the village.

—Mark 8:26

As they were coming down the mountain, he ordered them to tell no one what they had seen until after the Son of Man had risen from the dead.

—Mark 9:9

These commands raise questions. Did the historical Jesus truly speak this way? If so, what was he trying to avoid? And if he didn’t, why does Mark depict him this way?

What is clear is that this secrecy motif is strongest in Mark. Matthew and Luke (both of whom used Mark as a source) preserve some of the commands but soften them or reframe them. The Gospel of John removes the theme entirely; in John, Jesus speaks openly about his identity from the beginning.

In 1901, William Wrede offered an influential explanation for the so-called “Messianic Secret.” He argued that the historical Jesus did not publicly present himself as the messiah during his lifetime. After Jesus’ death, however, his followers began proclaiming him as the messiah. Wrede suggested that this would have created an obvious problem: if Jesus really was the messiah, why had no one heard about it while he was alive? Why hadn’t he said so himself?

According to Wrede, the Gospel of Mark resolves this problem by portraying Jesus as deliberately hiding his identity. The secrecy commands are not historical memories but theological devices meant to explain why Jesus’ messianic status was only recognized after the resurrection.

Wrede’s proposal is not widely accepted today. There are several problems with it. For one, the Gospel of Mark doesn’t seem to be written to convince outsiders; it’s written for people who already believe Jesus is the messiah. Mark assumes the reader accepts this from the very first line, and he never pauses to defend the claim or answer objections. That makes Wrede’s “public explanation” theory harder to sustain.

Furthermore, the Gospel of Mark is usually dated to around 70 AD and was likely written outside of Israel. Mark wasn’t writing for eyewitnesses, nor for people who could easily check his story against firsthand memory. His audience was already a generation removed from Jesus’ ministry, which makes it unlikely that he was trying to solve an immediate historical objection about what Jesus did or didn’t publicly claim.

So that doesn’t explain it. And now we’re back to our questions. Did Jesus actually say this? Why? Or did Mark invent this? Why?

One could argue that if we lack a convincing reason for Mark to invent this motif, it may well trace back to the historical Jesus. I think that’s reasonable, but it raises a harder question: why would Jesus do this at all? Wouldn’t he have wanted people to know he was the messiah? The usual explanation—humility—doesn’t fully work, since the text shows him sternly commanding silence, as if there were real consequences for speaking too soon.

Jesus certainly understood that certain titles carried political weight. Calling yourself “messiah” in first-century Judea often implied kingship, revolt, and a challenge to Roman authority. If word spread too quickly, before he controlled the context of the claim, the movement could have been crushed before it began. Even the Gospels hint at this dynamic—crowds swelling, authorities taking notice, tensions rising. Jesus was ultimately executed under the charge of claiming to be a king. That alone suggests he may have been navigating dangerous terrain, choosing carefully when and how his identity was revealed.

Many scholars today view the Messianic Secret not as a historical memory or an apologetic invention, but as a narrative strategy built into the Gospel of Mark itself. In this reading, secrecy is one of Mark’s tools for shaping how the reader comes to understand Jesus. Mark is not simply reporting events; he is constructing a pattern of delayed recognition, where Jesus’ identity emerges gradually and only becomes intelligible at a specific point in the story.

In Mark’s narrative world, the people who should understand Jesus—the disciples—repeatedly fail. They misunderstand his parables, fear his miracles, argue about status, and cannot grasp the idea of a suffering messiah. Meanwhile, the demons recognize him immediately, creating a kind of ironic contrast: cosmic forces know who Jesus is, while humans closest to him do not. The secrecy commands reinforce this dynamic. They slow down the revelation so that the reader and the characters never receive the full picture too early.

One possibility is that we don’t have to choose between these two suggestions. Jesus may well have discouraged certain proclamations during his ministry, especially if he understood the political danger of messianic language. And later, Mark could have taken that historical impulse and woven it into a deliberate narrative pattern, sharpening it and using it to guide the reader’s recognition of Jesus. In other words, the secrecy commands may be rooted in memory yet shaped into something more literary—a real habit of Jesus, reframed by Mark into a theological structure.

But once you leave the terrain of hard history, another set of questions opens up. Theological questions. What if the “Messianic Secret” isn’t only a literary device or a historical puzzle, but something that reflects the way Jesus still comes to us?

Maybe God left the historical Jesus a mystery on purpose. Maybe he allowed the Gospels to take the shape they did (and allowed only certain ones to survive) so that we would never stop searching. There’s only so much anyone can know for sure, and only so much we can know at all. But there is just enough to keep us looking, just enough to keep the questions alive. It leaves us turning the story over and over, thinking about Jesus the way he once argued and reasoned with other Jews, pulled into a lifelong conversation we can’t quite finish. Maybe this was God’s intention.

If we look at it that way, then I am following the will of God by searching for the historical Jesus, who will forever remain partially a secret.

I don’t know if any of that is true. I’m only wondering. But I do think the secrecy in Mark points beyond Mark. It raises the question of whether hiddenness isn’t just a feature of the text—but part of how Jesus continues to be found, or not found, now.

I love this idea that the secrecy encouraged by Jesus (but often ignored) in Mark’s Gospel might be based both on real memories and enhanced for literary effect. But even more I appreciate your suggestion that this is the way Jesus comes to us today. In secrecy. Partly shrouded in pious myth, partly elevated in theological frames, and also vibrantly present as the historic teacher from Nazareth — who is exalted by later believers to be equal to God the Father himself.

Great article thanks, great points. I think the only thing I would add is performing wonders and taking care of the poor made the religious elites look bad by contrast, complicating further the idea of messiah connotating political liberator—Jesus knew the kerfuffle he would cause

But yes, I think we are all really disconnected from the loaded implications of “Messiah” back in the day.

Two decades ago I wrote a song called “Messiah”, which wrestled deeply with spiritual struggle. I can see now that my use of that word was very “Christian”, ancient people would have looked at me very strangely