On the Term “Apocalyptic Prophet”

Why I’m Letting It Go

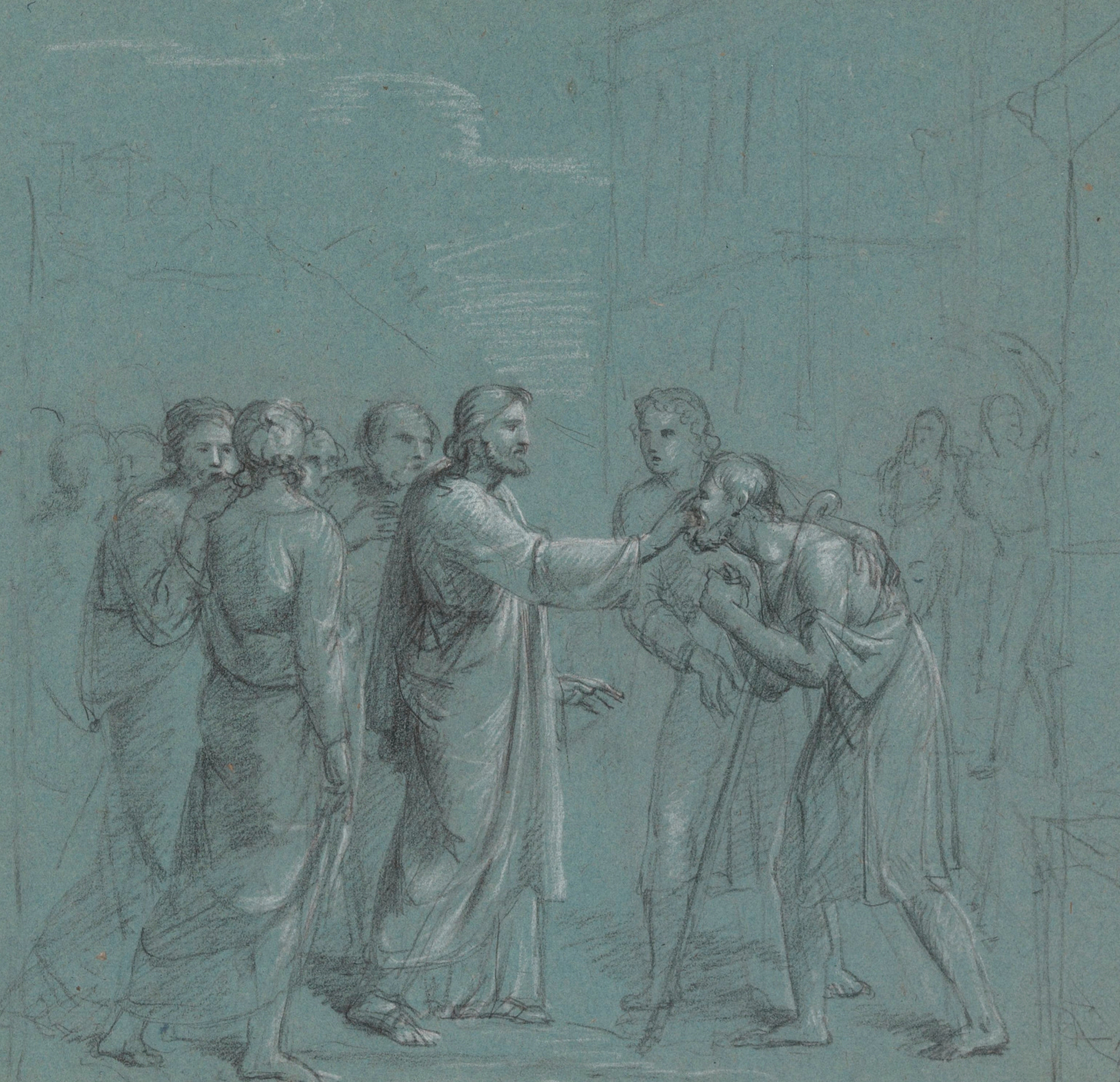

“Jesus Healing a Blind Man” - Jean Antoine Verschaeren

I might let go of the term apocalyptic prophet. It’s a common label for a prominent paradigm in historical Jesus studies. In simple terms, many scholars, for a long time now, think the real Jesus was an end-of-the-world preacher. None of these scholars think he was only an end-of-the-world preacher, but that end-of-the-world preaching was his main message—that mostly everything was organized around it. This is what’s usually called the apocalyptic prophet model. My favorite historian, Dale Allison, supports this model. Bart Ehrman, who’s probably the most famous Bible scholar right now, has a book called Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. According to Ehrman, the apocalyptic prophet paradigm was the dominant view among historical Jesus scholars for most of the 20th century.

I’ve gotten so wrapped up in historical Jesus studies that I’m starting to use its jargon without thinking about my audience. Philip Goff, a philosopher whose work I’ve enjoyed, did an AMA on here. I asked him, “Was the historical Jesus an apocalyptic prophet?” He clearly didn’t know what I meant. It was disappointing to realize I had asked someone I admire a bad question.

It got me thinking though—it’s an awfully narrow term, isn’t it? Apocalyptic prophet. As I write this, I’ve just finished rereading the Gospel of Mark for the who-knows-how-many-th time, and I found myself asking: how can you describe Jesus without calling him a healer? So much of the story is Jesus performing miraculous healings.

Now, like I said, proponents of the apocalyptic prophet model aren’t saying Jesus wasn’t a healer. They’re saying he was primarily an apocalyptic prophet.

Let me briefly explain why I think Jesus was apocalyptic. There are certain New Testament passages that sound as though the authors believed the end of the world was coming soon. Observe Paul:

For this we declare to you by the word of the Lord, that we who are alive, who are left until the coming of the Lord, will by no means precede those who have died…

—1 Thessalonians 4:15–17

And Mark has Jesus saying:

“Truly I tell you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the kingdom of God has come with power.”

—Mark 9:1

There’s also the fact that most major Christian denominations still believe in a coming end-of-the-world event—the Second Coming of Jesus. Christianity is currently an apocalyptic religion for many denominations, including my own Catholicism.

So, since Paul and the author of Mark (Matthew and Q as well) seem to think the end is near, it’s hard for me to imagine that the historical Jesus didn’t think the same. This expectation, after his death, became belief in his return—a belief that has been repeatedly delayed throughout Christian history. The alternative is that Jesus didn’t believe the end was near and that Mark 9:1 somehow emerged anyway. The former requires fewer interpretive gymnastics. There’s a lot more to it, but that’s a shortened version of why myself and many historians think Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet.

At this point it may sound like I’m arguing for the apocalyptic prophet model, when the purpose of this essay is to step away from it. I’m not denying that the evidence points toward Jesus believing the end was near. I’m asking whether that belief is enough to define him.

When we ask what’s happening throughout most of the Gospel narratives—what Jesus is actually doing—the answer isn’t primarily apocalyptic preaching. There’s also healing, exorcising, feeding crowds. Even as a skeptic, I think Jesus really was doing these things in some sense. I don’t think they were as miraculous as the way the Gospels describe, but I do think Jesus performed healings and that people believed they worked, whether they truly did or did not.

I even think it’s plausible that the historical Jesus “raised someone from the dead,” in the sense that someone appeared dead or nearly dead and later recovered, and that Jesus was credited with the recovery. Whether Jesus had anything to do with it or not, people came to believe he had raised the dead. That seems historically plausible to me.

So Jesus was a miracle worker. Does the phrase apocalyptic prophet really capture that? I don’t think it does. That’s why I may stop using it. But then what should I say instead? An apocalyptic miracle worker?

That leads to a question I don’t yet have a clear answer to: was there a connection between Jesus’ apocalyptic expectations and his miracles?

To even begin answering that, you’d need a theory of how Jesus understood himself within his apocalyptic worldview. My best guess is that he did see himself as the messiah and the Son of Man. I think he believed God and the Son of Man would descend from heaven, raise the dead, judge the living and the dead, condemn the wicked, and welcome the righteous into an earthly kingdom of God. Many scholars argue that Jesus did not see himself as the Son of Man. I tend to disagree. I think he spoke of the Son of Man in the third person as the Gospels record, but that it was understood among his followers that he was referring to himself. I also think he believed that when the kingdom arrived, he and the Twelve would hold positions of authority, with Jesus seated at God’s right hand. I think he believed he had a unique responsibility to proclaim the good news and lead the people into the coming kingdom.

So how do the miracles fit into this self-understanding? Apocalypticism explains the nature of his messiahship, but it doesn’t clearly explain his healing activity. One could say that, as an apocalyptic messiah or prophet, he therefore performed miracles, because that is what messiahs and prophets did—but that connects miracles to messiahship or prophecy, not directly to apocalypticism itself. The connection feels distant. And I’m not convinced one was clearly more important than the other. Arguably, the Gospel authors place more narrative weight on the miracles than on explicit apocalyptic teaching. That’s debatable, and it’s a question I’d like to explore further: what aspect of Jesus mattered most to each Gospel writer?

For now, I’m inclined to refrain from calling the historical Jesus an apocalyptic prophet. The label isn’t wrong, but it’s too narrow. It doesn’t adequately capture the figure I see in the sources—especially the traditions that remember Jesus, above all, as a miracle worker.

Works Cited

Allison, Dale C., Jr. Jesus of Nazareth: Millenarian Prophet.

Ehrman, Bart D. Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium.

The Holy Bible. New Revised Standard Version.

Love the post, Joseph! So much to discuss. Lots of great hits on target that open up beautiful new questions. This is what I love so much about your writings!

It should be noted that while Paul gave much of the content for 1 Thessalonians, it was mostly penned by the Silas (Paul confirms it himself), who also penned 1 Peter for Shimon ha-Kefa. (As I posted yesterday, I suspect Silas also penned the Epistle to the Hebrews.)

Generally, it’s something a categorical mistake to pair anything from Paul’s letters to the gospels, especially Mark and Matthew, but especially when they’re not actually discussing the same experience or “event”.

I genuinely think a better translation of Mark is needed as I think that the Greek, the Latin, and the English have done horrible linguistic and conceptual violence to the Hebrew cosmological rendering here.

“Truly I tell you, there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the kingdom of God has come with power.”

This is a standard translation, very common - totally incorrect.

“I insist to you that some here today, standing among you, will not [have] taste[d] death by the time the Commonwealth of YHWH has arrived with full authority.”

This is how I would more faithfully render this text from within a Hebrew-Yahwistic cosmological milieu rather than a Greek eschatological one. Theos, Deus, “God” is never the same as YHWH. Theos is a Goyim approximation for YHWH, but they are not the same: conceptually, ontologically, expressively.

More, it might be worth remembering that there is no “end” to the world in ancient Yahwistic cosmological structures. Yehoshua never believed or claimed that *the world was ending*. His chroniclers in the gospels spoke often about the “age” ending, but that is not Greek eschatology, it’s prophetic pattern-recognition within Yahwistic cosmological framings.

YHWH’s power last for all time, “the fullness of the age” - so how can the world, where YHWH’s active force is moving eternally, end? This is never addressed in Christian eschatological investigations.

Only entropy wants the world to end. Only entropy wants us to focus on an eschaton, and in doing so we help it accomplish its own telos.

YHWH exists, as Genesis 1 and John 3 make so abundantly clear, to prevent the end. To restore to life. To renew the world, not to end it. To transition from scarcity into abundance, from adversarialism to collaboration, from strife to peace - all through the Covenant.

My read on John is that he wants us to see that YHWH is attempting not to Jubilee a nation, as Moshe did, or even the whole of humanity, as Yehoshua did, but the whole of the Kosmos - every atom of the known and unknown universe, rescued from “formlessness and void”, restored and resurrected into the life of the Kosmos, for whom YHWH has radical agape (a love so powerful that it fuses two things together such that new life and power is generated in the fusion, the integration, the “holy” and “perfected”).

His gospel, after chapter 3, is demonstration after demonstration of Yehoshua performing this Kosmic restoration at a microcosmic level: among individuated humans, restoring them to community, to Covenantal rhythms and protections, through “commandment-keeping” (fidelity to Torah).

It’s very, very clear (with a decent translation) that Yehoshua believed that a major shift in the world’s operating systems was about to occur, and he was confident (or Mark, Matthew, and John were confident) that the Commonwealth of YHWH was about to break through.

And, textually, this “event” he was prophesying about is explained at Pentecost: “the Commonwealth of YHWH arriving with authority.”

What happens after Pentecost? The official founding of the Jerusalem Kehilla (“assembly”), the purchase of land outside town, the formation of the first community-village, etc.: the Commonwealth of YHWH arriving (authority at Pentecost, with the Breath of Wholeness manifesting as tongues of the Flame; since the flames didn’t hurt the Apostles, I presume the image is meant to invoke the same Flame as at the Burning Bush, conferring Messianic authority to the Twelve from Yehoshua and Yohanan).

It’s always tempting to think about “the end of the world” and its very, very easy to project OUR beliefs about this, which have been shaped by bad translations and worse theology for nearly twenty centuries - a hundred lifetimes of distance between us and them.

We are focused about the end of the world. He was not. He was focused on helping the vulnerable survive the transition of operating systems and restoring the immune system response to the virus of empire: Covenant.

I am still puzzled how we narrowed and redefined the term "apocalyptic" to mean "about the end of the world" when it means "unveiling." Before I went to church (regularly) at 23, I had come to believe that all the "end of the world" preachings by Jesus were pointing to the cross and resurrection, and the "judgment" was the "setting into order" that happened there. I have returned to this interpretation now in my later years.

I am aware that this means that Paul and some other early writers already misinterpreted Jesus' teaching. Or didn't they? What if we saw their writings in that way and in that connotation?